[magazine kave=Choi Jae-hyuk Reporter]

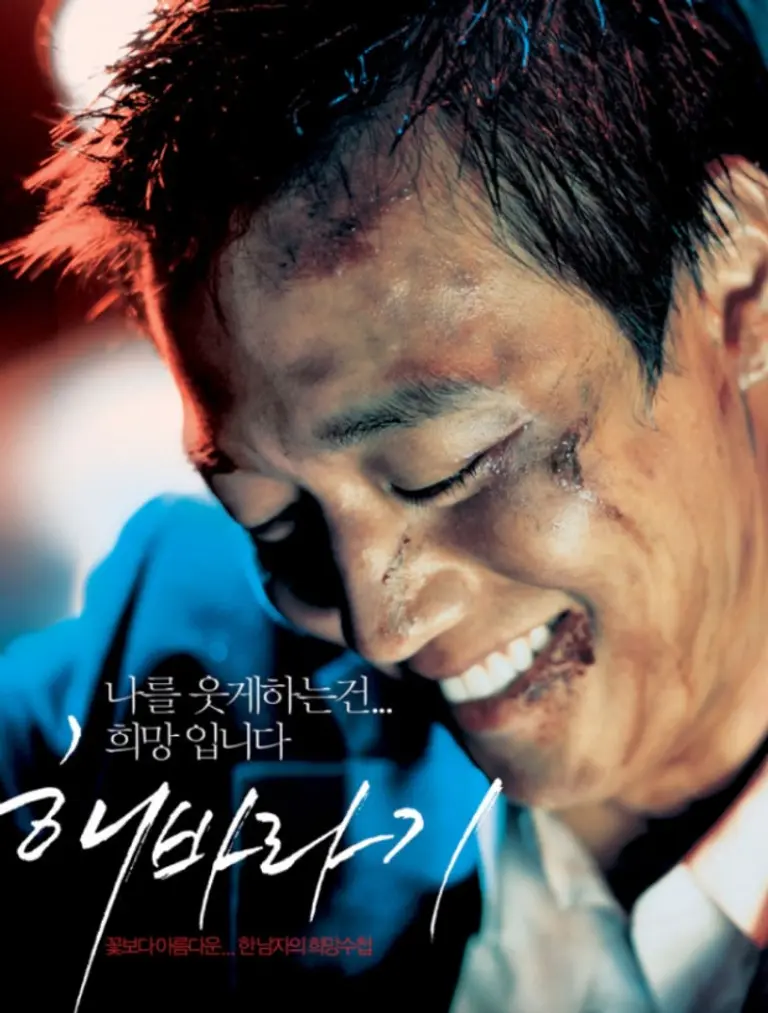

On the roadside of a narrow rural village, there is a shabby snack bar under a sign covered in grease. The movie 'Sunflower' begins with the footsteps of a man returning to that very restaurant. Oh Tae-sik (Kim Rae-won) was a gangster who rampaged with just his fists in his youth, but he ended up imprisoned due to a murder case. On the day of his release, he heads to the restaurant holding a bouquet of sunflowers. Years ago, the restaurant owner, an elderly lady who warmly fed him, had said, "Make sure to come back when you get out," and he returns to the old neighborhood like a time traveler, holding onto that promise. The fact that what the ex-convict brings is not a document envelope but yellow flowers already breaks the conventions of the genre.

The village appears quiet on the surface. The sunlight reflecting off the walls of old buildings, narrow alleys filled with familiar faces, and the scattered shops along the highway. However, a closer look reveals that this neighborhood is already infested with organized crime and local power. Like mold creeping behind wallpaper, violence has deeply penetrated the fabric of this town. Tae-sik's former gang still holds sway over the area, and local dignitaries like the hospital director, police, and county mayor are intertwined with invisible strings. Ordinary local merchants endure their days while keeping an eye on them. Tae-sik knows this structure but no longer wants to return to it.

Nevertheless, what he seeks is not violence but 'family.' The restaurant owner Yang Deok-ja (Kim Hae-sook) is not related by blood, but she is the only person in the world who treated Tae-sik like a human being. He recalls the letters and photos he received every year while in prison and hesitates in front of the restaurant for a while before finally opening the door, awkwardly like a middle school student on a first date. Inside, there is Deok-ja, who still smiles like a mother, and her straightforward and bold daughter Hee-joo (Heo Yi-jae). Tae-sik greets them with an awkward smile, but Deok-ja welcomes him as if they had just eaten together yesterday.

Before long, the restaurant is filled with various characters, including a new kitchen aunt, the loudest customers in the neighborhood, and a police officer who acts like a neighborhood big brother and a gangster detective. This space is not just a restaurant but serves as a kind of rehabilitation center and a second womb for Tae-sik.

A Meditation Diary of a Patient with Anger Management Disorder

Tae-sik's first goal is incredibly simple. He wants to control his temper, avoid swearing, not fight, and live while protecting the restaurant with his mother and Hee-joo. He sticks his 'resolution list' on the wall and deliberately adds a smile to the end of his sentences, fearing he might get angry. Like a bomb disposal team carefully handling a mine, Tae-sik tries to dismantle the violence within him piece by piece. Even when someone provokes him, in situations where he would have charged in with rage before, he forces himself to bow his head and repeatedly say, "I'm sorry."

Even when local punks cause trouble in the restaurant, he grits his teeth and endures, thinking of Deok-ja and Hee-joo's faces. The process is both funny and poignant. The sight of a large, tattooed man clenching his fists like a child reveals just how difficult it is for someone accustomed to violence to become ordinary. This is not just a story of redemption; it is a survival diary of a man negotiating with the monster within himself every day.

A World That Does Not Tolerate Peace

However, this neighborhood does not wait for Tae-sik's transformation. The former mid-level boss of his gang and his superiors feel uncomfortable upon hearing the news of Tae-sik's release. The fact that a once-legendary fighter is now washing dishes behind a snack bar appears to them as a potential threat and an ominous sign. It is as if a retired killer opened a bakery in the neighborhood; Tae-sik's ordinary life makes them even more anxious.

As Tae-sik becomes closer to the locals, attempts to draw him back into the criminal underworld and movements to eliminate him altogether intensify simultaneously. One day, as Tae-sik, Hee-joo, and Deok-ja return from shopping, they encounter a procession of black cars, which feels ominous, like a prelude to the tragedy that will unfold. The threat that follows a happy scene is the cruel editing style that director Noah often employs.

A Lifeboat Named Family

The film gradually builds up Tae-sik's daily life and his relationships with the locals until the middle. Scenes like gently sending a drunken customer away, Hee-joo playfully teasing Tae-sik about his past while cautiously observing the situation, and Deok-ja holding Tae-sik's hand and saying, "Let's start anew now" create small but warm ripples. The audience knows that this peace will not last long, yet they hope that Tae-sik can smile a little more like a 'sunflower.'

Therefore, from the point where the pressure from the organization overtly reveals its power and the reality of the violence that has taken over the neighborhood emerges, the atmosphere of the film changes dramatically. It is like a pack of wolves suddenly appearing during a pastoral picnic.

The structure where power and violence are intertwined operates cruelly against Tae-sik. The police are not all on Tae-sik's side either. Some individuals genuinely want to help him, but the game is already rigged at a higher level. No matter how much Tae-sik endures or tries to smile, his past is the easiest 'stigma' for local power holders to exploit. Eventually, a series of incidents occur, threatening the future of the people he loves and the modest restaurant they dreamed of.

From that point on, Tae-sik stands at the edge of a cliff, having to choose whether to let go of the emotions he has held back until now or to keep his promise until the end. The film races toward that final choice and the explosive consequences that follow, but it is better to face the tragic ending and catharsis through the work itself.

The Aesthetics of Genre Hybridization, or Tear Gland Terror

When discussing the artistic value of 'Sunflower,' the first thing that comes to mind is the way genres are combined. This film wears the shell of a typical gangster revenge drama, but at its core are a family melodrama and a coming-of-age story. It spends more time on the pain of those trying to suppress violence than on the thrill of violence itself, and it assigns more meaning to the resolution written on the wall and the sunflower picture in the corner of the restaurant than to the power of a fist.

The reason it has earned the nickname 'tear-jerker' is that the moments that make the audience tear up are not the scenes of bloodshed but the exchanged glances and a few words between a mother and son, or between siblings. This film is as precise as a sniper targeting the audience's tear ducts.

The character setting of Oh Tae-sik is exquisite. He possesses overwhelming fighting skills like a typical gangster hero, yet he is a complete failure socially. He has no educational background, no money, no job, and the only means to prove himself to the world is through violence. However, after his release, Tae-sik makes extreme efforts to detach that violence from himself. Like someone trying to cut off their own arm, it is painful but desperate.

The childlike aspects of him that emerge during this process, his immature language, and his awkward laughter evoke a strange protective instinct in the audience. Kim Rae-won's performance convincingly connects this duality. With just a glance, he can instantly evoke the shadow of a rough and dark past, yet in expressions where he shrinks his shoulders in fear of being scolded by his mother, he reveals the energy of an innocent boy. This dissonance is the driving force that creates the emotional energy of the film. It is like Rambo suddenly playing with dolls; that discordance creates intense emotions.

A Real Family with No Blood Relation

The character of Yang Deok-ja is also a crucial pillar. Deok-ja is not just someone who feeds Tae-sik. She is a presence that tells him, without asking anything or digging into the past, "What matters is you being here now." What this character shows is the answer to how a relationship without a drop of blood can become family. She treats Tae-sik with respect instead of pity and through actions rather than sermons.

Kim Hae-sook's unique warm yet strong performance elevates Deok-ja beyond the typical 'national mother' stereotype. Because of this character, Tae-sik's transformation feels like a genuine turning point in life rather than just a simple awakening or motivation for revenge. Deok-ja is not a superhero mentor to Tae-sik; she is just an ordinary mother who asks, "Have you eaten?" when he comes home. And that very ordinariness is the most supernatural ability for Tae-sik.

The direction intentionally does not shy away from 'corny emotions.' The camera often lingers obsessively on the characters' faces, showing their cries and screams as they are. The background music sometimes pushes the emotions to an excessive degree rather than supporting them delicately. This approach may seem outdated to audiences who prefer refined minimalism, like watching a melodrama from the 2000s.

However, 'Sunflower' persuades the audience with the honesty of its excessive emotions. By not hiding the small humor, excessive wailing, and the curses and screams that burst forth in extreme situations, the film chooses emotional resonance over genre perfection. This film does not pretend to be cool. Instead, it boldly asks if hiding emotions is not the stranger thing to do.

Action That Understands the Weight of Violence

The film's attitude is clear even in its depiction of violence. The action that appears on screen is not flashy by today's standards, nor is it intricately choreographed. Instead, each fight scene carries emotion. When Tae-sik finally swings his fist after holding back for so long, the audience feels a mix of exhilaration, relief, and deep sadness. The thought of 'this should not have happened' naturally follows.

The film does not consume violence as a mere tool for catharsis; it shows the psychological compression leading up to the explosion of that violence and the emptiness that follows. Thus, as the film approaches its climax, the audience finds themselves in a complex emotional state, applauding while feeling a heaviness in their hearts. It is like getting off a roller coaster and feeling queasy.

The recurring sunflower motif in the cinematography and art direction is also noticeable. From the paintings on the restaurant walls, bouquets, to the small decorations Tae-sik carries, sunflowers always hover around him. The sunflower symbolizes the 'light' that Tae-sik looks toward, representing the new life symbolized by his mother, Hee-joo, and this small restaurant. At the same time, the sunflower hints that Tae-sik cannot move forward without facing his past directly.

It is not a flower that only looks at the bright side; it is something Tae-sik must lift his head to see. The direction quietly places this symbolism in the background without flaunting it, adding to the film's lingering impact. The sunflower is like a GPS for Tae-sik, guiding him whenever he gets lost.

The Politics of Tear Buttons

One reason this film has been talked about for a long time is the 'moments of collective emotion' it creates. There are several scenes that are often referred to as 'tear buttons' on the internet, and when recalling those scenes, many people remember specific lines or gestures that made them tear up without realizing it. The scene where Tae-sik weeps while looking at the resolution on the wall, the moment Hee-joo tries to be strong for Tae-sik, and the words Deok-ja offers him all have the power to evoke tears even when the story is already known.

This power does not come from plot twists or tricks but from the film's attitude of wanting to understand and love the characters until the end. 'Sunflower' does not emotionally manipulate the audience; it honestly reaches out and says, "Let's cry together."

Of course, there are drawbacks. The story structure is quite conventional, and some supporting characters appear somewhat cartoonishly exaggerated. The villains tend to be consumed as functional characters symbolizing evil rather than being depicted with complex psychological depth. Like a boss character in a video game, they exist merely as obstacles for Tae-sik to overcome, lacking the portrayal of complex human beings.

For some audiences, this simplicity may help with emotional immersion, but for those expecting a multi-layered drama, it may leave a sense of disappointment. Additionally, as the latter half progresses, emotions and violence peak simultaneously, creating a feeling of being pushed into the next event before fully experiencing the lingering impact of each scene. Nevertheless, the reason this film continues to be mentioned over time is that even these drawbacks feel like a style intertwined with a specific emotional purity.

As time passes, 'Sunflower' has become a kind of 'emotional code' regardless of its box office performance. When someone says, "I cry when I watch Sunflower again," that statement carries a confession that goes beyond simple evaluation: 'I may not want to live like Tae-sik, Deok-ja, or Hee-joo in that movie, but I have come to understand their hearts.' The film pushes the simple truth that those who have not been loved have the right to be loved, rather than a sophisticated message.

It leaves the audience with the belief that even those with broken pasts can become someone's sunflower, while never giving up on that belief, capturing Tae-sik's face in memory. This film has become a kind of cultural shorthand, allowing people to check each other's emotional temperature with just the question, "Have you seen Sunflower?"

A Sunflower That Will Be By Your Side

If life feels too harsh and recent works seem increasingly calculated and cold, the rough and warm emotions of 'Sunflower' can provide comfort. Watching how a man, who is neither perfectly right nor perfectly cool, endures for the love and promise he barely holds onto, evokes something old within the audience. It is like discovering a dusty album in the attic.

Those who have gone through extremely difficult times may see themselves in Tae-sik's resolutions and hesitations, failures, and attempts at re-challenge. For those who prefer raw but honest tears and love over neat and sophisticated crime films, 'Sunflower' will surely remain memorable.

Above all, when the desire arises to be someone's sunflower at least once, simply revisiting this film can provide a small courage. Ultimately, 'Sunflower' is not a film about violence but a film about love. It is merely a story of a man who only knew how to express that love through his fists, knocking on a door for the first time with a flower in hand. And behind that door, someone is always waiting to say, "Welcome, let's eat," showcasing the oldest and most powerful fantasy.