The Darkness of an Era Where Characters Were Power

In 15th century Joseon, characters were synonymous with power. Chinese characters were more than just a means of notation; they were the impregnable fortress supporting the scholar-official class. Only those who mastered the difficult Chinese characters could pass the state examination and seize power, and interpret complex laws to dominate others. Illiterate commoners had no means to appeal even if they suffered injustice, and they could only look at the notices posted on government walls with fear, unable to understand whether they contained matters of life and death. Knowledge at the time was not something to be shared, but a tool of thorough monopoly and exclusion.

For the ruling class, the universalization of knowledge meant the loss of vested interests. The vehement opposition of scholars like Choi Man-ri to the creation of Hunminjeongeum was rooted in the arrogance of "Why share knowledge with the lowly?" and a fundamental fear that their sanctum might be invaded. They fiercely criticized it as "contrary to the duty of serving China" or "the act of barbarians," but the essence was the fear of the collapse of the class order. Literate commoners would no longer blindly obey.

The Limitations of Idu and the Disconnection of Communication

Of course, attempts to notate our language were not nonexistent. Idu, Hyangchal, and Gukyeol, developed since the Silla period, were desperate measures by ancestors to write our language by borrowing the sounds and meanings of Chinese characters. However, this could not be a fundamental solution. As revealed in Choi Man-ri's appeal, Idu had clear limitations as "recording natural language in Chinese characters, with variations in notation depending on region and dialect."

Idu was not a complete script but merely a 'half-baked' auxiliary means accessible only by overcoming the massive barrier of Chinese characters. To learn Idu, one still had to know thousands of Chinese characters, making it as unattainable as a pie in the sky for ordinary people. Moreover, Idu was a rigid style for administrative work, too crude and narrow to capture the vivid lives and emotions of the people, their songs, and laments. The imperfection of communication tools meant a disconnection in social relations, causing the 'arteriosclerosis of speech' where the people's voices could not reach the king.

Love for the People, Not a Slogan but a Policy... A Revolutionary Welfare Experiment

We praise Sejong as 'the Great' not because he expanded territories or built splendid palaces. Few leaders in history were as thoroughly focused on 'people' as Sejong. His love for the people was not an abstract Confucian virtue but manifested in radical social policies aimed at concretely improving the lives of the people. Among these, the 'maternity leave for slaves' system best illustrates the ideological background of the creation of Hunminjeongeum.

At the time, slaves were treated as 'talking beasts' and listed as property. However, Sejong's perspective was different. In 1426 (Sejong 8th year), he ordered that female slaves of government offices be given 100 days of leave after childbirth. But Sejong's meticulousness did not stop there. In 1434 (Sejong 16th year), he added 30 days of leave before childbirth, stating, "There are cases where mothers die because they cannot recover after giving birth and immediately returning to duty." A total of 130 days of leave, a groundbreaking period longer than the 90 days guaranteed by modern South Korea's Labor Standards Act.

Even more shocking was the consideration for husbands. Recognizing the need for someone to care for the mother, Sejong granted 30 days of leave to the husbands, who were also slaves, to nurse their wives. There is no record in any civilization, whether in Europe or China, of granting paid maternity leave to the husbands of slaves in the 15th century. This shows that Sejong recognized slaves not as mere labor but as 'family members' with inherent human rights. Hunminjeongeum is an extension of this ideology. Just as he gave slaves leave to protect their 'biological life,' he gave them letters to protect their 'social life.'

Asking 170,000 People... Joseon's First National Referendum

Sejong's communication method was not a unilateral top-down approach. He did not fear the process of asking the people's will when deciding on major national affairs. The anecdote of establishing the land tax law 'Gongbeop' proves his democratic leadership.

In 1430 (Sejong 12th year), when the Ministry of Taxation proposed a tax reform plan, Sejong conducted a public opinion survey asking for approval or disapproval from the people nationwide for five months. From officials to rural villagers, a total of 172,806 people participated in this vote. Considering that the population of Joseon at the time was about 690,000, it was a practical 'national referendum' with most adult men participating. The result was 98,657 in favor (57.1%) and 74,149 against (42.9%).

The regional response was interesting. In Gyeongsang and Jeolla provinces, which had fertile land, approval was overwhelming, but in Pyeongan and Hamgil provinces, which had barren land, there was more opposition. Sejong did not push through with a majority vote. He took several more years to devise a reasonable alternative (Jeonbun 6-grade law, Yeonbun 9-grade law) that considered the circumstances of opposing regions, varying taxes according to land fertility and annual yield. For a monarch who listened so attentively to the people's voices, the absence of a 'vessel' to contain their voices, a script, must have been an unbearable contradiction and pain.

Agony in the Deep Night, the Secret of Direct Rule

Sejong kept the process of creating Hunminjeongeum strictly confidential. The Annals of the Joseon Dynasty barely record the discussions on the creation of Hunminjeongeum, suddenly appearing in December 1443 with a brief record that "the king personally created 28 letters." This suggests that anticipating the backlash from the scholar-officials, the research was conducted secretly, led by the king and royal family, without even the scholars of the Hall of Worthies knowing. In his later years, Sejong suffered from severe eye disease and diabetes complications. Even in a situation where he could hardly see, he stayed up nights to create letters for the people. Hunminjeongeum was not the result of a genius's inspiration but the product of a sick king's devoted struggle, sacrificing his life.

Ergonomic Design... Modeling the Articulatory Organs

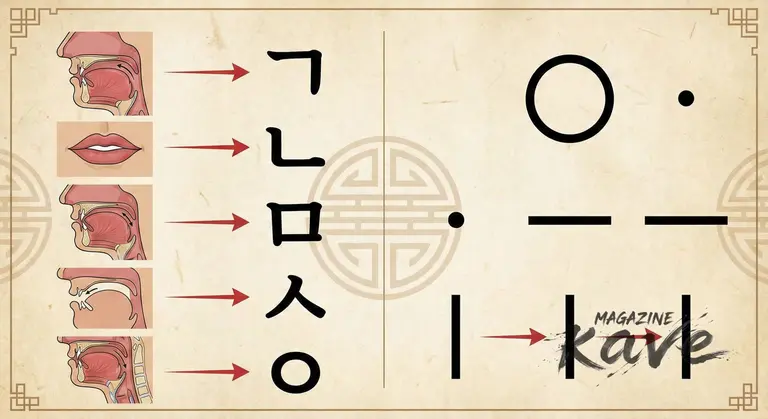

Hunminjeongeum was created based on the unprecedented principle of 'modeling the articulatory organs' in the history of world scripts. Unlike most scripts that imitate the shapes of objects (pictograms) or are derived from existing scripts, Hangul visualizes the biological mechanism of sound production in humans as a 'map of sound.' The 『Hunminjeongeum Haerye』 clearly explains this scientific principle.

The five basic consonants of the initial sound were drawn as if taking an X-ray of the oral structure when pronounced.

Velar (ㄱ): The shape of the tongue root blocking the throat (the initial sound of 'gun'). This accurately captures the articulation position of the velar sound.

Alveolar (ㄴ): The shape of the tongue touching the upper gums (the initial sound of 'na'). It visualizes the tip of the tongue touching the alveolar ridge.

Bilabial (ㅁ): The shape of the mouth (the initial sound of 'mi'). It imitates the shape of the lips closing and opening.

Dental (ㅅ): The shape of the teeth (the initial sound of 'sin'). It reflects the characteristic of the sound where air escapes between the teeth.

Glottal (ㅇ): The shape of the throat (the initial sound of 'yok'). It represents the shape of the sound resonating through the throat.

Based on these five basic characters, the principle of 'adding strokes' according to the intensity of the sound is applied. Adding a stroke to 'ㄱ' makes the sound stronger, becoming 'ㅋ', and adding a stroke to 'ㄴ' makes it 'ㄷ', and adding again makes it 'ㅌ'. This makes sounds of the same phonetic series (sounds with the same articulation position) have morphological similarities, a systematic system that modern linguists admire. Learners can intuitively deduce the rest of the characters by mastering just the five basic characters.

Heaven, Earth, and Man... Vowels Containing the Universe

If consonants modeled the human body (articulatory organs), vowels contained the universe in which humans live. Sejong designed the vowels by embodying the Neo-Confucian worldview of Heaven (天), Earth (地), and Man (人), the three elements.

Heaven (·): The shape of the round sky (the basis of positive vowels)

Earth (ㅡ): The shape of the flat earth (the basis of negative vowels)

Man (ㅣ): The shape of a person standing on the earth (the basis of neutral vowels)

By combining (synthesizing) these three simple symbols, numerous vowels were created. When '·' and 'ㅡ' meet, it becomes 'ㅗ', and when '·' and 'ㅣ' meet, it becomes 'ㅏ'. This is the pinnacle of 'minimalism,' expressing the complex world of sound with the simplest elements (dots, lines). Moreover, the philosophical message that man (neutral) harmonizes between heaven (positive) and earth (negative) shows that Hangul is not just a functional tool but embodies humanistic philosophy. This vowel system is so future-oriented that it is directly applied to the input method of modern digital devices (Cheonjiin keyboard). It is the intersection where the philosophy of 600 years ago meets today's technology.

Choi Man-ri's Opposition Appeal... "Are You Trying to Become Barbarians?"

On February 20, 1444, seven scholars, including Choi Man-ri, the vice-minister of the Hall of Worthies, submitted a joint appeal opposing Hunminjeongeum. This appeal is a historical document that starkly reveals the worldview of the ruling elite at the time and their fear of the creation of Hangul. Their opposition logic can be summarized into three main points.

First, the justification of serving China. They argued that "creating an independent script is something only barbarians do and will invite ridicule from the great nation (Ming China)." For them, civilization meant belonging to the Chinese character cultural sphere, and deviating from it was a return to barbarism. Second, the concern for the decline of scholarship. They viewed it from an elitist perspective, arguing that "since Eonmun is easy to learn, if people learn it, they will not study difficult subjects like Neo-Confucianism, and the number of talented people will decrease." Third, the political risk. They claimed, "Moreover, there is no benefit to the principles of governance... it is indeed detrimental to the citizens' studies."

However, what they truly feared was the 'easy script' itself. As Jeong In-ji revealed in the preface, "The wise can understand it before the morning is over, and even the foolish can learn it in ten days." If writing becomes easy, everyone will know the law, and everyone will express their thoughts. This meant the collapse of the 'information' and 'interpretive power' monopolized by the scholar-officials. Choi Man-ri's appeal was not mere conservatism but the pinnacle of vested interest defense logic.

Sejong's Counterattack: "Do You Know Phonology?"

Sejong, who usually respected his subjects' opinions and was a king of debate, did not back down on this issue. He rebuked Choi Man-ri and others, asking, "Do you know phonology? Do you know how many initials and finals there are in the four tones and seven sounds?" This shows that Sejong designed Hangul not as a mere 'convenience tool' but as a highly scientific system based on phonological principles.

Sejong suppressed the scholar-officials' 'serving China' justification with the greater justification of 'love for the people,' saying, "Isn't Seol Chong's Idu meant to make the people comfortable? I also intend to make the people comfortable." He had a clear political purpose of allowing the people to avoid unjust punishments (dissemination of legal knowledge) and express their will through Hangul. This was one of the most intense intellectual and political struggles in the history of the Joseon Dynasty.

Yeonsangun's Suppression and the Survival of Eonmun

After Sejong's death, Hangul faced harsh trials. Especially the tyrant Yeonsangun feared the 'power of accusation' that Hangul possessed. In 1504, when anonymous letters criticizing his misdeeds and immorality were written in Hangul and posted everywhere, Yeonsangun was furious. He immediately issued an unprecedented 'ban on Eonmun,' ordering that "Eonmun should neither be taught nor learned, and those who have already learned it should not use it." He collected and burned all Hangul books (book burning) and tortured those who knew Hangul. From this time, Hangul was demoted from its official status to being disparaged as 'Eonmun (vulgar script)' and 'Amkeul (script used by women).'

Reviving Voices... The Script Preserved by the People

However, even the blade of power could not cut out the script that had already permeated the tongues and fingertips of the people. Women in the inner chambers recorded their lives and sorrows in Hangul through Naebang Gasa (inner chamber lyrics), and the Buddhist community translated scriptures into Hangul (Eonhae) to lead the propagation among the people. Commoners laughed and cried while reading Hangul novels and communicated through letters. Even within the royal family, queens and princesses secretly exchanged Hangul letters, and kings like Seonjo and Jeongjo also enjoyed using Hangul in private correspondence.

The people picked up and embraced the script that power officially abandoned. This proves that Hangul is not a top-down script but one that took root in the lives of the people and gained vitality from the bottom-up. This tenacious vitality later became the driving force to overcome the greater ordeal of the Japanese colonial period.

The Japanese Colonial Period, the Policy of Eradicating the Korean Language, and the Korean Language Society

In 1910, when Japan usurped national sovereignty, it thoroughly suppressed our language and script as part of its 'policy of eradicating the Korean nation.' From the late 1930s, it completely banned the use of Korean in schools and forced the use of Japanese (national language policy), and even changed names to Japanese-style through the Soshi-kaimei policy. In the desperate crisis that the spirit of the nation would disappear if the language disappeared, the 'Korean Language Society' was formed, centered on the disciples of Ju Si-gyeong.

Their sole goal was to create a 'dictionary' of our language. Creating a dictionary was an act of gathering scattered words, setting a standard, and declaring linguistic independence. This grand project, which began in 1929, was called the 'Malmoe (gathering words) operation.' It was not the work of a few intellectuals. The Korean Language Society appealed to the people nationwide through the magazine 〈Hangul〉. "Please send us your local dialects." Then a miracle happened. Men and women of all ages from all over the country sent their dialects, native words, and indigenous words to the Korean Language Society. Thousands of letters poured in. This was not just a collection of vocabulary but a nationwide linguistic independence movement in which the entire nation participated.

The Sacrifice of 33 People and the Miracle of the Seoul Station Warehouse

However, Japan's surveillance was relentless. In 1942, Japan fabricated the 'Korean Language Society Incident' by seizing on a phrase in a student's diary at Hamheung Yeongsaeng High School that said, "I was scolded for using the national language." Thirty-three key scholars, including Lee Geuk-ro, Choi Hyun-bae, and Lee Hee-seung, were arrested and severely tortured. Teachers Lee Yoon-jae and Han Jing died in prison.

Even more tragic was the fact that the 'Korean Language Dictionary' manuscript of over 26,500 pages, painstakingly collected over 13 years, was confiscated as evidence and disappeared. Although liberation came in 1945, the dictionary could not be published without the manuscript. The scholars were despondent. Then, on September 8, 1945, a miraculous event occurred. A bundle of papers was found abandoned in a corner of the Seoul Station's Chosun Transport Warehouse. It was the 'Korean Language Dictionary' manuscript that Japan had intended to dispose of as waste paper but had left behind.

The bundle of manuscripts buried in the dust of the dark warehouse was not just paper. It was the blood of the martyrs who tried to protect our language even under torture, and the earnest wishes of the people who had lost their country, written letter by letter. Without this dramatic discovery, we might not be enjoying the rich and beautiful vocabulary of our language today. This manuscript is now designated as a treasure of South Korea, testifying to the fierce struggle of that day.

The Script Closest to AI... Sejong's Algorithm

In the 21st century, Hangul stands at the center of another revolution: the era of digital and artificial intelligence (AI). The structural characteristics of Hangul remarkably align with modern computer science. Hangul has a modular structure that combines elements (phonemes) of consonants and vowels to form syllables. By combining 19 initial consonants, 21 medial vowels, and 27 final consonants, it can theoretically express 11,172 different sounds. This gives it an overwhelming advantage in information input speed and processing efficiency compared to Chinese characters, which require separate input and coding for tens of thousands of complete characters, or English, which has an irregular pronunciation system.

Especially in the processing and learning of natural language by generative AI, Hangul's logical structure has a significant advantage. Thanks to its regular principles of character creation (pictographic + adding strokes + synthesis), AI can easily analyze language patterns and generate natural sentences with relatively little data. The 'algorithm' that Sejong designed with a brush 600 years ago is blooming again today in cutting-edge semiconductors and servers. Hangul is not just a legacy of the past but the most efficient 'digital protocol' for the future.

A World-Recognized Documentary Heritage... An Asset of Humanity

In 1997, UNESCO designated Hunminjeongeum as a 'World Documentary Heritage.' Although there are thousands of languages and dozens of scripts worldwide, Hangul is the only script where the creator (Sejong), the time of creation (1443), the principles of creation, and the manual (Hunminjeongeum Haerye) explaining its use remain intact in their original form.

This is a global acknowledgment that Hangul is not a script that evolved naturally but an 'intellectual creation' meticulously planned and invented based on high intellectual ability and philosophy. Nobel Prize-winning author Pearl S. Buck praised Hangul as "the simplest yet most excellent script in the world," and said, "Sejong is Korea's Leonardo da Vinci." It is no coincidence that the UNESCO award for individuals or organizations contributing to literacy is named the 'King Sejong Literacy Prize.'

Sejong did not create Hangul merely for the practical purpose of enabling the people to write letters and learn farming methods. It was to return 'voice' to the people. To let them shout when wronged and record when unjust, liberating them from the prison of silence, was a radical declaration of human rights.

The same goes for the Korean Language Society martyrs during the Japanese colonial period, who risked their lives, and the common people nationwide who sent their dialects in crumpled letters. It was not just about making a dictionary. It was a desperate struggle to protect the 'spirit' and 'soul' of the nation suffocating under the imperial language of Japanese. Today, the reason we can freely send messages on smartphones and leave our opinions on the internet is thanks to the blood and sweat of those who fought against power and endured oppression for 600 years.

Hangul is not just a script. It is a record of love that began with "pitying the people," and the prototype of democracy that aimed to make everyone the master of the world by "making it easy for everyone to learn." But are we taking this great heritage too much for granted? In modern society, there are still silences of the marginalized. Migrant workers, people with disabilities, the poor in Korean society... Are their voices being properly conveyed to the center of our society?

The world Sejong dreamed of was one where all people could fully express their will. When we not only take pride in Hangul but also record and represent the 'lost voices of the present age' with this script, the spirit of the creation of Hunminjeongeum will be completed. History belongs not only to those who record it but to those who remember, act, and shout it out loud.