![Lee Jae-yong delivers a welcome speech at the gala dinner held on January 28 (local time) at the Smithsonian Arts and Industries Building in Washington D.C. [Magazine Kave=Park Su-nam]](https://cdn.magazinekave.com/w768/q75/article-images/2026-01-29/c22e931e-0ed2-4f10-8a7c-f5220c8090fb.jpg)

On January 28, 2026, Washington D.C. was a space where the cold fog of the Potomac River intersected with the static weight of the federal government’s stone buildings. However, that evening, the temperature inside the Smithsonian Arts and Industries Building (AIB), located in the heart of the National Mall, soared to a different dimension of heat. This historic building, which symbolized the 19th-century American industrial revolution as the 'Palace of Wonders', was glowing not with electric energy but with the aesthetic brilliance condensed from 5,000 years of Korean history. The gala dinner celebrating the successful conclusion and closing of the traveling exhibition 'Korean Treasures: Collected, Cherished, Shared', donated by the late Lee Kun-hee, was not just a corporate event. It was a grand epic showing how a family's determination saved the soul of a nation and how the Eastern philosophy that embraces 'emptiness' encountered the Western 'filled desires'.

To understand the resonance of this historic night, one must first trace the chronology of the venue. The Smithsonian Arts and Industries Building is the second oldest building among the Smithsonian museums, designed by Adolf Cluss and Paul Schulze, and opened in 1881 with a ball celebrating the inauguration of President James A. Garfield. Built to accommodate 60 carloads of exhibits brought from the 1876 Philadelphia World’s Fair, this building was a space proving America’s technological genius, progress, and civilization. The presence of a 1,500-year-old Buddha statue and a Joseon moon jar sent from 21st-century Korea in this space dominated by 19th-century industrial rationalism was a massive metaphor in itself.

In the Rotunda Plaza where the gala dinner was held, the spot where the massive 'Statue of America' once stood holding Edison’s light bulb was now filled with prominent figures from both the political and business sectors of Korea and the United States, facing the essence of Korean aesthetics. The guest list itself was a map of global power. Leading the attendees were Secretary of Commerce Howard Rutnik, along with key figures from the U.S. Congress such as Ted Cruz, Tim Scott, and Andy Kim, as well as designers of technological supremacy like Wendell Weeks, Chairman of Corning, Gary Dickerson, CEO of Applied Materials, and Jerry Yang, co-founder of Yahoo. They momentarily set aside their cold rationality discussing the fine processes of silicon wafers and shared a human sense of awe in front of the heavy rock mountains of Inwangsan, seemingly imbued with moonlight, and the curves of white porcelain.

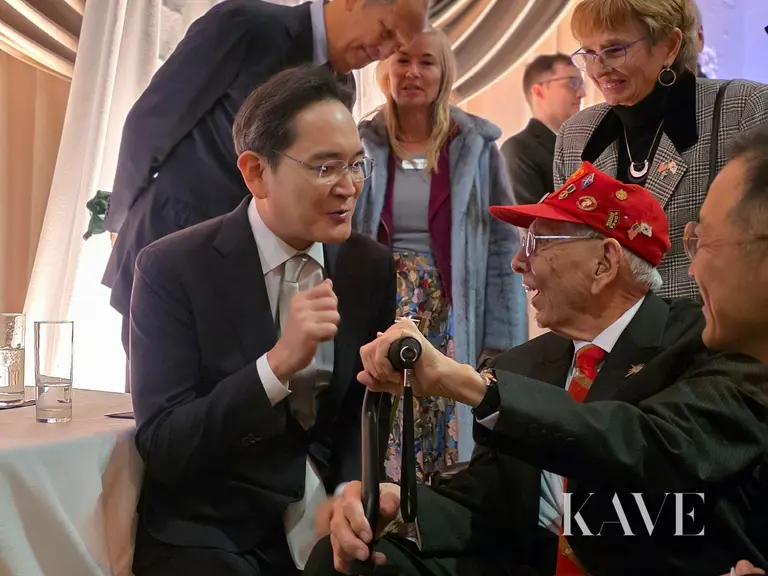

Notably, many congress members from Texas and South Carolina, where Samsung's production bases are located, attended in large numbers. This suggests that the Lee Kun-hee Collection plays a pivotal role in private diplomacy that strengthens the bonds of 'hard power' (semiconductors, electronics) through 'soft power' beyond mere cultural enjoyment. In his speech, Lee Jae-yong, Chairman of Samsung Electronics, stated that the prosperity of modern Korea would not have been possible without the sacrifices of 36,000 American veterans over 70 years ago, showcasing a sophisticated rhetoric that elevates the debt of history into cultural exchange. Among the guests were four veterans of the Korean War, including Rudy B. Mikins, symbolizing a touching moment where past blood allies evolved into future cultural partners.

Walter Benjamin defined the act of collecting as a 'struggle against dispersal'. For collectors, ownership is the most intimate relationship one can have with an object, and collectors believe they live within the items. Amid the loss of sovereignty and the devastation of war that 20th-century Korea had to endure, Korean cultural heritage was on the brink of being scattered across the globe. The collections of Lee Byung-chul, the founder, and Lee Kun-hee, the late chairman, were not merely a hobby of collecting expensive antiques but a desperate cultural liberation movement to preserve and protect the 'aura' of a vanishing nation.

The Lee Kun-hee Collection is astonishing not only for its vast number of over 23,000 items but also for the 'will to preserve' contained within it, which carries even greater weight. When the Samsung family donated this vast collection to the nation in 2021, it was recorded as a 'national contribution' signifying a transition from private ownership to public sharing. At the gala dinner, Honorary Director Hong Ra-hee reflected on the process of expanding the collection from ancient artifacts to modern masterpieces, emphasizing how the identity of Korean art connects not only with past relics but also with contemporary avant-garde art. The exhibition held at the Smithsonian NMAA was the first overseas fruition of that donation, surpassing 65,000 cumulative visitors and setting a record as the largest exhibition of Korean art to date.

Among the numerous treasures on display, the Baekja Daeho moon jar resonated most powerfully with American audiences. This jar, representing the restrained beauty of Joseon’s Neo-Confucianism from the 17th to 18th centuries, embodies the philosophy of 'Yeobaek' instead of ornate colors or gilded decorations. Yeobaek is not just an empty space; it is the 'fullness of emptiness' intentionally left for the viewer's gaze and heart to linger.

The moon jar is not a perfectly spherical shape. Due to its large size, two hemispheres must be separately crafted and joined, and the inevitable asymmetry and traces of the seams that occur in this process breathe life into the jar. British philosopher Alain de Botton praised the moon jar as a 'supreme tribute to the virtue of humility'. Unlike the Western aesthetic of symmetry that demands perfection, the moon jar affirms human imperfection and offers a sense of relief that 'it’s okay for everything not to be perfect'. This 'natural indifference' resonates with the healing aesthetics that modern people crave, and the fact that moon jar-related merchandise sold out at the exhibition's souvenir shop is a result of this widespread empathy.

Art critics refer to the moon jar as the 'jar that swallowed time'. Just as the clay from 200 years ago is reborn as a new entity on a modern canvas, the moon jar in the Lee Kun-hee Collection is not a relic of the past but an ongoing source of inspiration. This is why contemporary artists like Kwon Dae-seop reinterpret the moon jar, exploring the boundaries between existence and absence, form and emptiness.

If the moon jar symbolizes the inner self of Koreans, Jeong Seon’s 'Inwangjesaekdo' shows a revolution in the perspective of Koreans looking at the external world. Painted in 1751 when Jeong Seon was 76 years old, this masterpiece is the pinnacle of 'True-view landscape painting'. Before Jeong Seon, painters imitated the idealized landscapes of China, imagining famous mountains they had never visited, but Jeong Seon captured the actual landscapes of Joseon right beneath his feet with his brush.

Inwangjesaekdo depicts Inwangsan right after the rain has cleared. The wet granite rocks settle heavily in dark ink color, while the mist rising between the valleys contrasts with the dazzling white of the empty space. This is not just a landscape painting; it is a visual manifestation of the Silhak movement that arose among Joseon intellectuals at the time, a subjective declaration to discover the unique value of 'our own' while breaking free from Chinese influence. The repetitive ink lines used to express the texture of the heavy rock mountains seem to foreshadow modern abstract techniques, delivering a powerful visual shock to contemporary audiences across 200 years.

This Smithsonian exhibition was particularly special because it did not hesitate to make bold attempts to connect classical art with modern pop culture. A 19th-century lion-shaped drum stand, occupying a corner of the exhibition hall, was a ceremonial tool of Buddhist temples, but it approached American MZ generation viewers with an entirely different meaning. They discovered the character 'Derpy' from the animated series 'KPop Demon Hunters', which took Netflix by storm in 2025, in the humorous expression of this lion.

Directed by Maggie Kang, this film tells the story of the K-pop girl group 'Huntrix' defeating ghosts through song and dance, and the numerous monsters and guardian deities appearing in the film were inspired by the images of the Tiger and Magpie or tigers in folk paintings included in the Lee Kun-hee Collection. The tiger, which was depicted foolishly in folk paintings to satirize the authoritative yangban, has come back to life on the 21st-century screen, forming a global fandom. This is a perfect example of how high art nourishes popular culture and proves that K-culture is rooted in a deep historical tradition.

The early sellout of 'moon jar' lights and 'Inwangjesaekdo' souvenirs at the exhibition entrance is not merely a matter of material desire. It signifies that Korean aesthetic identity has established itself as a 'phenomenon' transcending generations and borders, from teenage girls who are enthusiastic about 'Huntrix' to middle-aged individuals moved to tears by soprano Jo Sumi's aria.

The underlying strategy of 'cultural diplomacy' is hidden behind this gala dinner led by Lee Jae-yong. The conversations exchanged in the hall were as intricate as the seams of ceramics, discussing the sophisticated semiconductor supply chain and AI ecosystem. Wendell Weeks, Chairman of Corning, mentioned the half-century partnership with Samsung, evaluating that this collection is not merely a listing of artworks but an embodiment of the passion for creation that has positively impacted the world across generations.

This process establishes Samsung as a cultural leader, transcending the role of a mere hardware manufacturer, preserving humanity's memory and designing future values. When American political figures gaze at the ink lines of Inwangjesaekdo, they realize Korea's resilience, and the trust in Samsung's semiconductor investments solidifies in unseen ways. This high-level network enhancement, where soft power (art) lends legitimacy and trust to hard power (technology), is likely one of the ultimate goals the Lee Kun-hee Collection aimed to achieve through its donation.

The successful prologue at the Smithsonian is just the beginning. The global tour of the Lee Kun-hee Collection is now heading to Chicago, the industrial center of America, and London, the treasure trove of human culture. The exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, starting in March 2026, will showcase how modern paintings from the Lee Kun-hee Collection converse with masters of Western modern art like Matisse and de Kooning. In September, the British Museum will present the essence of Korean aesthetics to European audiences.

This grand narrative is like an unending flow. The 'loss of aura in the age of mechanical reproduction' that Walter Benjamin feared has instead been transformed into a 'universal diffusion of aura' through the Samsung Art Store. The digital brushstrokes of Inwangjesaekdo broadcasted on the living room TV screens of tens of thousands of households around the world do not tarnish the nobility of the original but practice a 'democratic aesthetics' that allows all humanity to possess the beauty of Korea in their own spaces.

On the night of January 28, 2026, the aria of Jo Sumi that flowed from the gala dinner in Washington filled the ceiling of the empty Arts and Industries Building. It was akin to the thoughts of the viewers filling the empty interior of the moon jar. The true message conveyed by the Lee Kun-hee Collection to the world is not 'What do we have?' but rather an answer to 'What have we preserved?'

These artifacts, which existed as evidence of resistance during times of national suffering and as a philosophy of sharing during periods of prosperity, are now transforming into a heritage of all humanity beyond the boundaries of Korea. The flexibility of Korean art, which can contain broader interpretations due to the existence of empty spaces (Yeobaek), is akin to the last 'fortress of the soul' that humanity must protect in this desolate age of technology. The aesthetic horizon opened by the Lee Kun-hee Collection will continue to shine with white light amidst the skyscrapers of Chicago and the fog of London, becoming a golden seam that firmly binds humanity's history together.