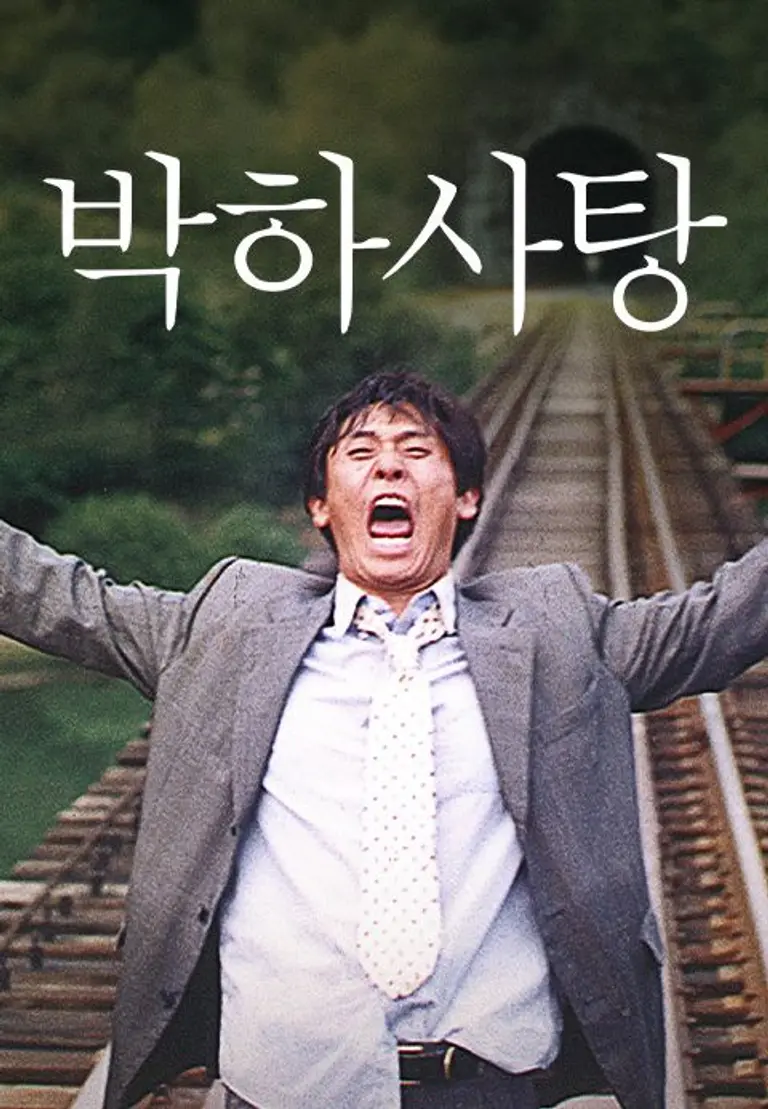

Camping chairs are set up by the riverside next to the railway. Friends from a club, reunited after 20 years, are about to share old memories. As drinks are passed around and old songs begin to play, a man in a tattered suit stumbles into the group. Kim Young-ho (Seol Kyung-gu). Friends who once pressed the camera shutter with him recognise him. But the sight of this man now seems to visualise the phrase 'life shatters into pieces'. He suddenly pushes people aside and jumps onto the railway. As headlights approach from afar, Young-ho screams towards the sky.

Screams, horns, and the deafening roar of a steel monster rushing in. The film 'Peppermint Candy' begins with the life-and-death catastrophe of one man and then embarks on a bold attempt rarely seen in film history. It turns the gears of time backwards.

Where the train has swept through, time flows back three years. In the spring of 1996, we see Young-ho barely surviving as a salesman for a small to medium-sized enterprise. He repeats the cycle of commuting to and from work, but his eyes resemble a dead fluorescent light. His relationship with his wife is effectively over, and he does not hesitate to harass a female employee from a client company while soaked in alcohol. The outbursts that erupt during company dinners and the excessive anger that makes those around him wary define Young-ho during this period as a man of uncontrollable emotions. The audience naturally begins to wonder, 'Was this man a monster from birth?'

Once again, the sound of a train is heard, and time slips back to the autumn of 1994. It was a time when the real estate speculation frenzy engulfed the nation. Young-ho boasts a little money in front of his friends, but there is a strange emptiness in his voice. As real estate deals go awry and conflicts arise with clients, he hardens into a sharper and more aggressive human type. He has not completely collapsed yet, but cracks have already spread throughout his inner self. The key question is where this crack began.

In 1987, Kim Young-ho, having taken off his military uniform, is still in the midst of the state violence system as a police officer. In that year, when the cries for democratization filled the streets, he faces student activists in an interrogation room as an investigator. Standing on the desk to look down at his opponents, and using torture and beatings like a manual among colleagues, Young-ho becomes the most 'diligent' perpetrator. The glint of a steel pipe under fluorescent lights, droplets of blood splattered on the back of his hand, the tightly bound face of a suspect. These scenes show how much of a 'model public authority' he was. However, even when sitting at home with his wife after work, he ultimately cannot open his mouth. Instead, silence, rampage, and sudden anger become his emotional language.

Time climbs back again. In the spring of 1984, Young-ho, a rookie police officer just given his badge. This shy and awkward young man is initially taken aback by the rough methods of his seniors. But he quickly learns that he must adapt to survive in this organisation. If he refuses violence, he becomes the target. In an organisational culture mixed with hierarchy and performance pressure, Young-ho transforms into a 'capable police officer'. From this point on, he disconnects his emotions to protect himself and becomes a machine that only executes orders.

However, the root of all this tragedy is revealed once again with the sound of a train. In May 1980, Young-ho is deployed to an unfamiliar city as a martial law soldier. Amid the chaos of confronting demonstrators, he unintentionally pulls the trigger and collides with a young girl's life. That moment is etched into his mind as an indelible scar. The scent of peppermint candy swirling from the end of the gun, the scene where blood, tears, and sunlight are mixed and congealed in memory. After this incident, he can never return to being 'the Young-ho of before'.

The film's destination finally reaches the spring of 1979. Young-ho, a high school senior who is neither a soldier, a police officer, nor an office worker, is holding a camera by the riverside. It is the day of the photography club's picnic. There, a girl named Yoon Soon-im (Moon So-ri) in a white skirt shyly smiles at him. Young-ho awkwardly hands over the camera, and Soon-im takes a peppermint candy from her pocket and places it in his hand. At that moment, an infinite possibility opened up between the two. But the audience already knows. This boy is destined to shout, "I want to go back" on the railway. The film persistently gazes at this gap. The details of the ending will be left for the audience to confirm themselves. What matters is the weight that this reverse-flowing time builds up in our hearts.

The past time that has supported your life

This film is structured in seven chapters that move backwards from 1999 to 1979. Each chapter bears poetic titles like 'Spring, The Way Home' and transitions with the sound of an approaching train. Thanks to this structure, instead of tracking the downfall of a human being in chronological order, we first confront the completely destroyed outcome and then trace back the causes with the perspective of an investigator. Just like in a CSI drama, where we first see the crime scene and then rewind the CCTV, we piece together why Young-ho became such a vile and violent person and at which point he crossed an irreversible line.

As time travels backwards, the tone of the screen subtly brightens, and the expressions of the characters become increasingly softer. The Young-ho of the late 90s is a broken office worker, a divorced man, a failed speculator, always soaked in irritation and fatigue. The Young-ho of the 80s is a part of the state violence apparatus. But the Young-ho of 79 has a transparent gaze and an awkward smile. Director Lee Chang-dong does not simplify the human inner self through this layered structure. He emphasises the fact that everyone was once someone who liked someone and dreamed of taking photos by placing the most beautiful scene right after the most tragic one. Like a cruel fairy tale.

The character Young-ho is both an individual and an allegory of 20 years of modern Korean history. The trajectory from the youth of 79 to the martial law soldier of 80, the police officer of 87, and the office worker of the neoliberal system in the 90s precisely overlaps with the collective trauma that Korean society has undergone. Young-ho is both a victim and a perpetrator of the era. As a martial law soldier and investigator, he trampled on the lives of others, and the memory of that violence ultimately destroys himself. The film does not shy away from this duality but gazes directly at it. It does not stop at condemning the morality of the 'bad individual' but also brings the institutions and times that mass-produced such individuals to trial.

The title 'Peppermint Candy' thus pierces the heart even more sharply. Peppermint candy is the small white candy that Yoon Soon-im handed to Young-ho, as well as the scent of first love and guilt that Young-ho will carry for the rest of his life. Like the cold and sweet sensation unique to peppermint, that memory makes his heart ache while constantly evoking an irreversible past. In the film, peppermint candy appears somewhat casually, but it operates like a kind of red alert for the audience. It signals that another irreversible choice is about to unfold.

‘Master’ Lee Chang-dong's masterpiece

The direction layers detailed symbolism onto Lee Chang-dong's unique cold realism. Rather than dragging characters along with long takes, the editing rhythm is impressive as it shows only what is necessary and then cuts sharply. Especially in scenes set in interrogation rooms, military trucks, and on the railway, the camera almost locks the characters in an unshakable fixed position. The density of despair and violence with no escape route is indelibly stamped on the audience's retinas. Conversely, in the riverside photography scenes or club meeting scenes, flexible camera movements and natural light bring the air of youth to life. Even in the same location, subtle differences in light and sound across time periods allow the audience to physically experience the texture of time.

Seol Kyung-gu's performance is the core element that makes this film a landmark in Korean cinema history. He convincingly portrays the process of a single actor transforming from a 40s wreck to a fresh young man in his 20s, not through makeup or special effects, but through the weight of his body, voice, and gaze. The Young-ho of 99 has drooping shoulders, heavy steps, and resignation in every word. When he beats a student in the interrogation room, his eyes no longer see a human being. In contrast, the Young-ho of 79 stutters and cannot even make eye contact in front of someone he likes. It is a spectrum that is hard to believe is the same actor. It almost looks like three different actors are performing in relay. Yoon Soon-im, played by Moon So-ri, has a limited amount of screen time, but she is the source of the cool lyricism that envelops the entire film. Her smile and trembling voice leave an imprint on the audience like a first love.

The political and social questions posed by the film are also clear. The violence wielded by martial law soldiers, police, company superiors, and colleagues is always wrapped in the guise of 'orders' and 'work'. Young-ho could choose at every moment, but he is also someone who could not choose. Every time he stands on a desk looking down at a suspect, holds a gun in a martial law truck, or is dragged into a superior's entertainment gathering and forced to wear an unknown smile, he gradually gives up on himself. The film demonstrates through its reverse structure that the accumulated total of this abandonment ultimately explodes into a scream on the railway.

The reason this work has been loved for decades is that it does not leave behind mere emptiness in tragedy. Of course, it is light-years away from a 'happy ending'. However, the youth by the riverside that reaches the end by moving backwards poses a strange question to the audience. If this young man had been born in a different era, or if he could have made different choices, would his life have changed? The film does not provide an easy answer. Instead, it makes each audience member reflect on the era and choices they have lived through. In that process, questions like 'Is there a little Young-ho inside me?' and 'What if I had taken a different path at that crossroads?' quietly arise.

If you want to see the truth buried beneath the heart

For audiences accustomed to light entertainment and fast-paced narratives, 'Peppermint Candy' may initially feel somewhat burdensome. It does not follow a structure where events occur and explanations follow; rather, it shows the already broken outcome and then slowly dissects the causes, requiring concentration. However, if you want to witness how a human being collapses with the times, what they lose in that process, and what they ultimately cannot let go of, there are few films as intricate as this one.

For those who want to feel the emotional temperature of modern Korean history in the 80s and 90s not through news clips or textbooks, but through the memories of a single human being, this work provides an intense experience. Words like martial law soldiers and demonstrators, interrogation rooms and company gatherings, and the ruins of the IMF are not abstract concepts but live and breathe as the memories of a single individual. For generations that did not directly experience that era, it offers clues to understand why their parents' generation seemed so solid yet had cracks somewhere.

For audiences who enjoy deeply immersing themselves in the emotional lines of characters, it will be hard to get up from their seats even after the ending credits have rolled. The sunlight by the riverside, the dust on the railway, and the lingering scent of peppermint candy will linger for a long time. 'Peppermint Candy' ultimately conveys this message: that everyone has wanted to shout "I want to go back" at some point. However, if there is a film that gives you a chance to reflect on your life and era before actually walking onto the railway, it is this work.